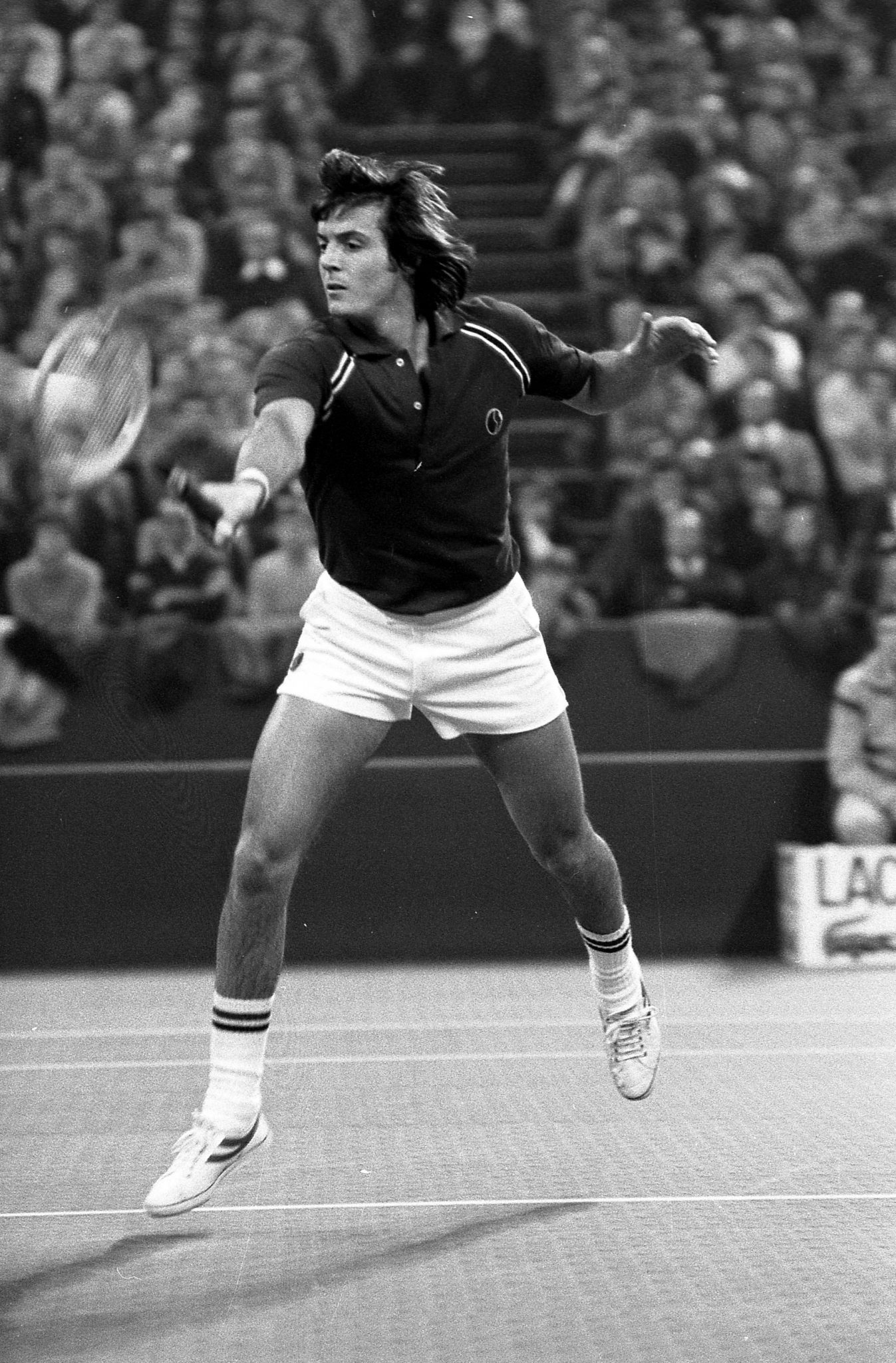

For Italian tennis fans, Adriano Panatta is a name that stands alone. Italians don’t just care about winning ― we value a combination of strategy, demonstrated renown on the court, and charisma and appeal outside the court. Adriano has all these qualities, making him a timeless icon internationally, and especially so in Italy.

Panatta was born in Rome in 1950, and he grew up with strict tennis training. In fact, Ascenzio, his father, worked as a keeper at the Tennis Club Parioli. And so it was destiny.

The little boy began to get a hold of the game, progressively gaining confidence with rackets, balls, and clay courts, beginning to hit the ball for hours against the wall. This young, omnipresent boy was called “Ascenzietto” by the other players, who soon knew his name.

It didn’t take long for Panatta to climb the national rankings ― he played his first Australian Open in 1969, then drew national attention in 1970 after winning the national open. His opponent was formidable; Nicola Pietrangeli was one of the best Italian tennis players of all time, was 17 years older than him, and was the winner of the last three years of the tournament (he had won it a total of seven times).

Their confrontation was also, inevitably, a generational one. Pietrangeli incarnated the elegant, classical style, while Panatta gave voice to the arising new style, with a higher rhythm, aggressive net play, and an overall more offensive and risky strategy.

The following year they faced each other again in the final, with the young champion winning again. He ended up winning the Italian Championship six times, the reigning champion until 1975.

Panatta’s tennis play went beyond Italian borders to land in international competitions. The victories continued to stream in: in 1971 he won the Senigallia Open, the first of his 10 individual titles. But the difference between reportage and his legend began to be differentiated in 1976. In his own words:

“At ‘Roland Garros’, I played the best tennis game of my life, after beating my rival at his match point, and leaving Borg behind at the quarter finals. I had sixty seconds of happiness at the end of the finals against Solomon and that was it. By the gala dinner, I was already very sad, having a feeling of emptiness. I had a sort of depression that lasted for the following three weeks.”

During that season Panatta brought a sort of grace to his game that wielded historical results: three victories, one at the Internazionali d’Italia (in his hometown Rome), one at the Roland Garros, and one at the Davis Cup.

During that fabulous year (1976) his first title was a victory at the Internazionali d’Italia, the most important clay tournament in Italy, and the second most important internationally after Roland Garros. Panatta said after the tournament:

“To plan a tournament you really need to know the city where it’s played very well. Rome is a big ‘slut’ ― during my ‘Internazionali’ it was like being married to both sport and glamour, tennis champs, and Romans.”

On his way to the final victory he defeated Newcombe, an Australian tennis player, who was number one in the 1974 world ranking and had seven individual Slam victories; and Vilas, an Argentinian player who was the first seed of the competition, number two in the world in 1975, and won four Slams during his career.

“I didn’t dedicate that victory to my father, my mother, my wife, or my son. I dedicated that victory just to myself!”

A few weeks later came the Roland Garros, a tournament so important that winning it alone would be enough to create a legendary tennis player. It was played on clay ― clearly Panatta’s favorite surface.

In France, he won against Solomon in the final round, becoming the second Italian (after Pietrangeli) to win a Slam. However, his most truly impressive game came during the quarterfinals, where he faced Borg, a myth and the first-seeded player in the tournament, and beat him in just four sets.

This wasn’t a new feat for Panatta: the two also encountered each other in 1973, when he had won as well. These two matches made Panatta the only tennis player capable of eliminating Borg from the French Open, a tournament won 6 times by the Swedes. Panatta spoke about the Swedish champion:

“I’d like to play every game against him because I feel like I couldn’t lose.”

Between them, a long-lasting friendship has flourished. At the end of the year came the Davis Cup. In 1976, the ultimate competition between teams took place in Chile under Pinochet. In Italy, a debate broke out over the opportunity to participate in the cup. Panatta said:

“The committee responsible for the PCI Sport Ignazio Piratsu told us the news: for Berlinguer we had to go to Chile. The political situation ― Pinochet regime ― made our decision pretty difficult to make. The Andreotti government said that Coni was free to decide whether or not we were actually allowed to win the game. At the end, we found ourselves in Santiago, ready to play. This was all thanks to Berlinguer.”

The Italian team was staffed by Panatta, Barazzutti, Bertolucci, and Zugarelli, with Pietrangeli serving as a captain, not just a player. The team won against Chile 4-1, capturing the first Davis Cup for Italy.

Panatta made himself the lead for the challenge: during the doubles game, he convinced his partner Bertolucci to wear red t-shirts as forms of protest. They came back in blue t-shirts in the last set.

His career continued successfully, winning three more individual trophies. He had a final loss in Rome against Borg, an elimination in the quarterfinals in Wimbledon and three more Davis Cup finals, which were all ultimately lost by the Italian national team. He retired in 1983, at age 33.

Forty years later, Panatta remains the best tennis player of the Open era, and his adversaries agree on one thing for sure: he could have won even more trophies, if only he committed himself to the game more. This is an idea that two of the greats (Borg and Pietrangeli) share about Panatta:

“Panatta is a player that could represent a constant nightmare for McEnroe, Connors, or me. But he’s not consistent.” And Pietrangeli: “Adriano was born to play tennis. It’s a pity that he lasted so short of a time, otherwise he would have been able to break all of my records.”

And so the Roman champion had a reputation for being a “lazy talent,” which probably make him even more fascinating and human.

“Their role model couldn’t be me. I was pure talent. But if you make it at the international level, well, you can’t be lazy. And I wasn’t. The thing was people thought of my Roman roots as being inherently lazy. It just happened that, after three full months of tournaments, I felt like doing something outside tennis. Tennis wasn’t the only thing in my life.”

Maybe that’s why he lost all the trophies from his victories: Panatta never wanted to be a role model, forced to live in the public eye and the shadow of his own legacy. Looking always ahead, running towards the net, looking for the winning strike ― Panatta never looked back.