It was the summer of 1922 at the Hotel Cavour in Milan, and two lovers were separated by only a couple of rooms, and seventeen years apart.

“I forgive him for having exploited, ruined, and humiliated me. I forgive him for everything because I was in love.”

Born in 1858 to a modest family of actors in Vigevano, Eleonora Duse began to act as a child, seducing audiences all over the world with her modern style of acting. Far from the common style of nineteenth-century, Duse’s performances were full of subtle nuances; shading her words with pauses and silences.

Eleonora gave an immediate impression of reality and ignoring the traditions of acting at the time, lived and breathed her characters to truly encapsulate the spirit of her roles.

“She was more than beautiful. She had an opaque paleness and olive skin, a solid forehead hidden beneath black locks, serpentine eyebrows, and beautiful eyes with a captivating gaze.”

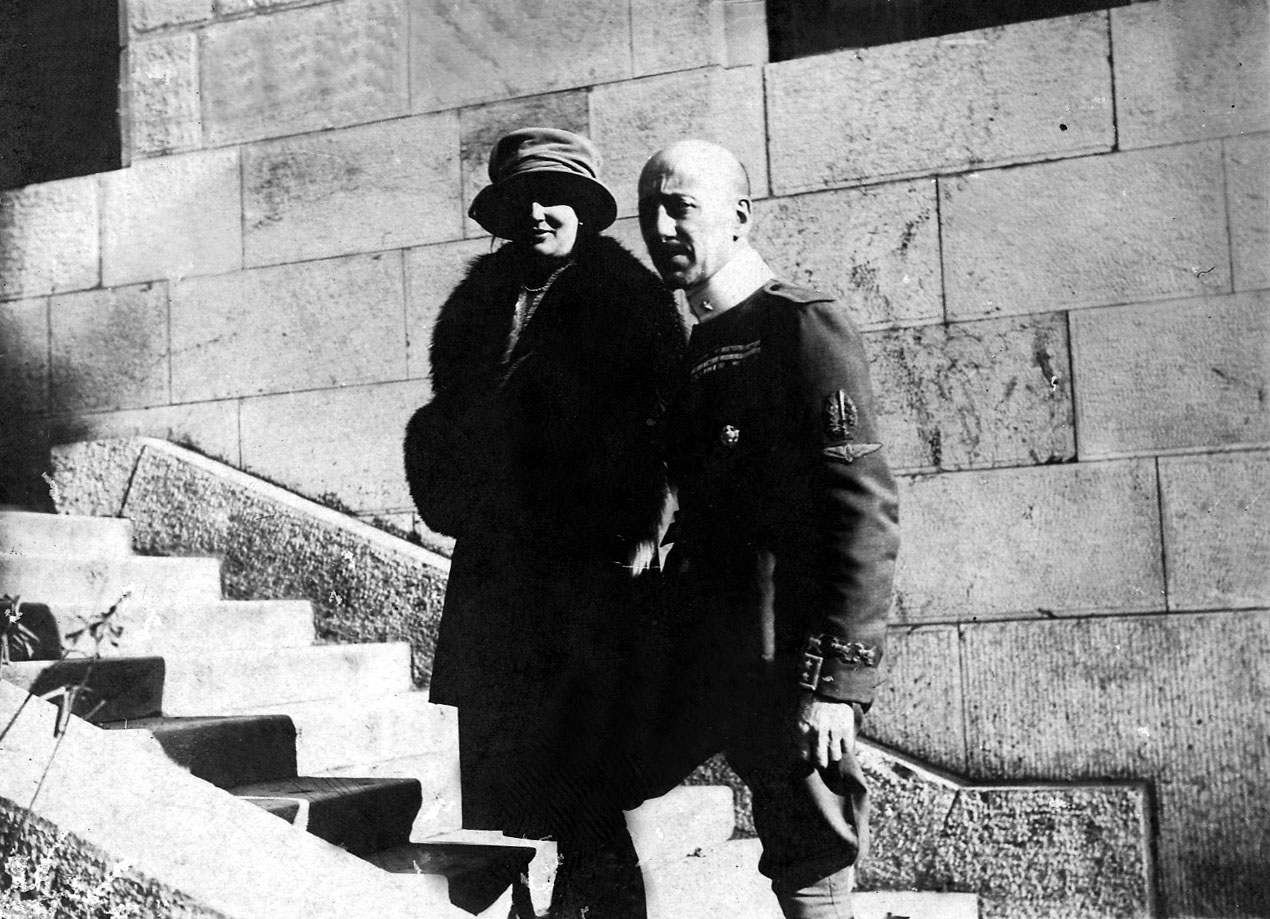

Rich and independent, restless and far from fragile, Duse fed her legend by rarely indulging journalists, instead preferring the company of artists and intellectuals. It is curious, therefore, that in 1882 a “little wolf from Abruzzo,” who loved worldly divertissements and lyrical decadence, tempted her.

Five years younger, not very tall but still very good looking, and a smooth talker, Gabriele D’Annunzio was a proper Casanova with a passion for the art of seduction. He set his sights on conquering the famous Eleonora who, at least initially, wasn’t tricked by his games.

“I would rather die in a corner than love a soul like that. I detest D’Annunzio, but I love him.”

Embarrassed by the advances of D’Annunzio, Eleonora denied him. However, in 1895, the Diva finally gave in and the two quickly became lovers.

D’Annunzio portrayed her as his muse; the actress, in turn, was enchanted by his fiery prose. Bored by the stale predictability of her line reading, Elenora asked the poet to write for her.

During these years of feverish work and moral abandon, Gabriele rented a gorgeous villa ― called the Capponcina ― in Settignano, near Florence. It was not far from Porziuncola, where Eleonora lived at the time.

The two lovers exchanged correspondence with an overwhelming passion. In the hundreds of pages between them, she constantly forgave him for his repeated betrayals.

“Do not talk to me about the empire of reason, about your carnal life, about your thirst for joyful life. I am full of these words!”

For several years, the writer saw her just as “a safe” in which to entrust his genius (and his own myth). In fact, he dedicated his first tragedy ― La città morta, originally composed for Duse ― to the famous Sarah Bernhardt, the artistic rival of Eleonora. He even blamed her for the failure of his play Il sogno d’un mattino di primavera, which was labeled by critics as “presumptuous and unbearably boring.”

Elenora still did not disown him― full of love for the Vate (prophet), the Divina (goddess) endured everything, even a vile representation of her that D’Annunzio created in his novel Il Fuoco. Foscarina, the character he based on Elenora, was a lascivious and cynical representation of her.

“I feel all the forces flowing in you but I do not know how to swim with you in deep water. You are the strongest.”

Again we return to the summer of 1922 at Hotel Cavour in Milan, and the two lovers are separated by those seventeen years since their last goodbye. But it is too late. Eleonora had already given up on Gabriele in 1904 when he had entrusted his fortunes from his play La figlia di Iorio to the young and attractive Irma Grammatica.

Alone and tormented, Duse renounced the theatre, never returning except for a final performance in Ibsen’s Ghosts. All the while D’Annunzio conquered women until he eventually decided to lock himself away, withdrawing from the world.

Eleonora Duse died in Pittsburgh on April 21st, 1924 during a tournée, far from her affections and from the places she loved. A few miles to the east, at his residence in the Vittoriale, Gabriele D’Annunzio looks at the relics in his studio: old globes, Sistine prints, Moroccan-bound books. Finally, he stops in front of a veiled bust; he lifts a scarf to expose its face. One last glimpse for the Vate of his Divina.

“She is dead, the one that I did not deserve.”