On 26 November 2018 Bernardo Bertolucci, the last great Master of Italian cinema, passed away. Born in Parma on 16 March 1941, over his fifty-year career he portrayed his age with meticulous passion, enhancing its most evident and marked traits and highlighting its silent and almost hidden qualities (and shadows) at the same time.

Stepping boldly into the traumas, fervors, disillusionments and contradictions of his contemporary society, Bertolucci marked the twentieth century and was then branded by it.

He was revered as a cult director, and then treated like a heretic for his most controversial film, Last tango in Paris (1972). Despite the shame of censorship, however, the author’s histrionic impetus never ceased to bring excellent results, constantly opening up to dialogue with the most diverse forms of art and expression.

“Cinema contains all other languages: architecture, literature, painting, sculpture, music, poetry, theater,” Bertolucci used to say, showing his comprehensive culture.

From his idol (and friend) Jean-Luc Godard, tireless experimenter trying to merge cinema and painting, he inherited an elegant and unmistakable taste for pictorialism.

But it is above all thanks to the association with the great director of photography Vittorio Storaro that the entire filmography of Bertolucci is full of images of rare iconographic beauty, with sublime references to figurative arts (and not only).

In The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), for example, the roaring tigers by painter Antonio Ligabue are the background to the headlines; but even more evident is the tribute to René Magritte’s surrealism, to ‘Golconde’ (1953) in particular.

Bertolucci and Storaro stage an unsettling and destabilizing pattern of figurative repetitions, aimed at underlining the dual and ambiguous scheme on which the entire feature film is built (see, for instance, the fact that Giulio Brogi is called to play two different characters, father and son, and therefore to embody the individual’s duplicity and inner conflict).

However, it is with The Conformist (1970) that the Bertolucci-Storaro association gives birth to a scenographic painting representing a unicum in the history of Italian cinema (perhaps in world cinema).

“Film Directors and directors of photography compose a visual and living mosaic in which full and empty, lights and shadows, black and white, perfectly fit.”

An urban fabric in which apparently majestic spaces and buildings turn out to be uninhabited: non-places in which figures of absence move around, in an overall design that echoes the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio De Chirico, Mario Sironi’s Novecentismo and Art Nouveau.

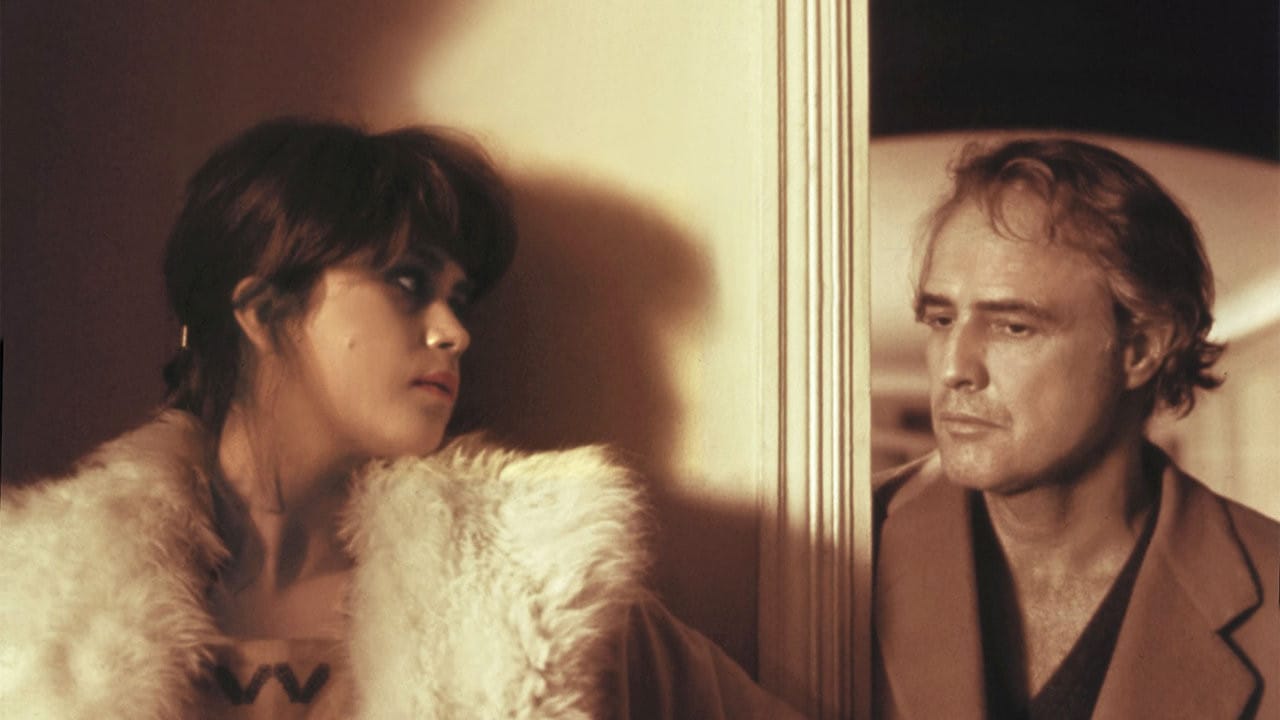

Francis Bacon is, instead, the beating heart of the film universally considered Bertolucci’s film maudit: Last Tango in Paris (1972).

Thirtyone at the time, the filmmaker played the expert and invited Vittorio Storaro, Marlon Brando, the costume designer and the set designer to the Grand Palais in Paris, where the first exhibition entirely dedicated to Bacon was hosted:

“I realized that during those visits the secret heart of the film was born. It seemed to me that an alarming sense of danger had remained in the film from the influence that Bacon had on all of us,” Bertolucci himself recalls in his diaries.

Distortion and depersonalization, essential elements in Francis Bacon’s creative processes, relive in Bertolucci’s work through the characters of Paul (Marlon Brando) and Jeanne (Maria Schneider), two strangers, self-deprived of their names and identities, who are called to reinterpret the carnal despair of the scrambled and torn bodies represented by the Irish-born artist.

Bacon’s influence (his triptychs, specifically) returned thirty years later in The Dreamers (2003) a manifesto film of a new cinephile generation (both young and nostalgic) that finds its own motionless driving force in citationism.

Apart from cinema tributes, the film recalls the romanticism of Eugène Delacroix, here combined with a pop taste for Andy Warhol ― ‘Liberty Leading the People’, made contemporary by the iconic face of Marilyn Monroe, translating the myth of Revolution into a pure dimension of mass and custom ― in this case full of erotic (and mortuary) impulses.

The painting portraying Isabelle and Matthew in their sleep, and their interweaving naked and voluptuous shapes, the choice of warm and exotic colors (and the specter of the attempted suicide at the hands of Isabelle) recall one of the most famous oils of the French painter, ‘The Death of Sardanapalus’ (1827).

But the most famous iconographic reference is certainly another one: “the marvelous and sensual appearance of Isabelle as ‘Venus de Milo.’”

Bertolucci takes a further step here: he looks at ancient classical art and, contemporary Praxiteles, transforms actress Eva Green’s body into an (im)perfect living sculpture. Marble was made flesh, releasing eroticism from the chains of immobility.