We all know Fellini. You need only mention a few titles to bring his cult scenes to mind. La dolce vita, 8½, Amarcord… Few, however, know that his cinema had its roots in the art of drawing, in humorous cartoons, even in the vaguely erotic and comic sketches he gave his wife Giulietta Masina.

Federico’s just a dream,

a time machine;

all that’s left around

is a scarf against the wind

…a leaving train.

There: Federico Fellini is here, in Antonello Venditti’s lyrics from his song Fellini, in 1982.

These are just a few words, but they are worth more than the many pages dedicated to the director born on 20 January 100 years ago. “Federico is a dream” (the song says): each of his films makes us live dreamlike and visionary atmospheres. He is “a time machine”: he has always put the Eden of childhood at the center of his films. And he is “a scarf against the wind”: because his red scarf has become the iconic trait of every director.

And that same red scarf is around the neck of his alter ego Marcello Mastroianni on the cover of a comic book by the great Milo Manara: Viaggio a Tulum, born from the collaboration between the two creative geniuses. The comic strip contains everything dear to Fellini, like Cinecittà, where most of his visions took shape, where Giulietta Masina (in La Strada), Anita Ekberg (in La Dolce Vita) and his alter ego Marcello Mastroianni, (the protagonist in most of his films) would wander.

Fellini was not only a formidable director, but he was also – all his life – a tireless cartoonist – and inspired many cartoons himself.

Until 28, Fellini mainly drew vignettes to get by.

He left Rimini for Rome, and at the end of the 1930s he stopped off in Florence, where he worked at the Nerbini publishing house: there he worked as a proofreader, a humorous writer, a draftsman, and wrote the scripts for some of Flash Gordon‘s comic strip stories. For Nerbini, Fellini also worked as a cartoonist at the satirical newspaper Il 420. Then, once he arrived in Rome, he worked at Marc’Aurelio, a humorous periodical that was an excellent training ground for future directors and screenwriters such as Cesare Zavattini and Ettore Scola.

Both the cartoons for Nerbini and those for the Marc’Aurelio were simply signed with his name, Federico. They have in common a strange surreal vein and immediately made “Federico” a leading signature. They enjoyed success (and Fellini enjoyed the money they earned him) and put the young designer in the circle of the most influential creative Romans. Fellini began to collaborate on films by comedians such as Erminio Macario, wrote the lines for Aldo Fabrizi’s live shows and began to write film and radio scripts.

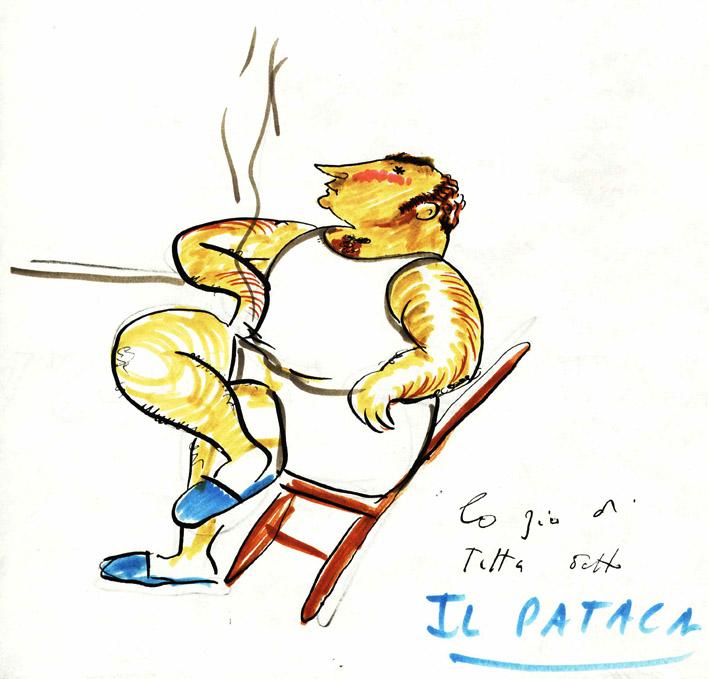

Cinema – as his main activity – arrived only at the beginning of the 1940s, after he had met Roberto Rossellini who introduced him as a screenwriter among the collaborators for Roma città aperta. From then on his main road was the screen. But Fellini wouldn’t stop drawing. On the contrary, drawings marked the genesis of every one of his feature films: they took shape in the storyboards of his films, which he always made himself. Like the “patacca” in Amarcord (pic above) or the dancer in 8½.

«Why do I draw the characters in my movies? Why do I take ‘graphic’ notes of their faces, noses, mustaches, ties, handbags, the way they cross their legs, of the people who come to visit me in the office? Because it’s a way to start looking the movie in the eye, to see what kind of ‘guy’ it is. It’s an attempt to look at something, even if it’s tiny, bordering on insignificance, but it seems to me it has something to do with the film, and covertly it tells me something about it…»

Sometimes he would collaborate with great artists. For the films Il Casanova and La città delle donne, for example, he drew with the French painter Roland Tropor, a man who always smoked Cuban cigar and who set up the same anxieties that Fellini would tell in his films in his surrealist paintings.

Federico and Roland exchanged impulses and suggestions and discussed ways to load scenes of everyday life with universal symbols.

Fellini and Tropor also worked together on another very strange project: Il viaggio di G. Mastorna, also known as Fernet (a feature film Fellini cherished a lot), in whose screenplay he also involved the writer and painter Dino Buzzati. The project took form, but not as a film: in 1992 it inspired a comic strip of the same name by the great Milo Manara, later printed by the publishing house by Il Grifo.

The plot, oneiric and visionary, is pure Fellini style. Everything revolves around a certain Giuseppe Mastorna, known as Fernet, a famous clown who, after traveling the world with the circus, finds himself in a city in Northern Europe. Stranded in a snowstorm, he becomes involved in surreal situations, like when he witnesses the dance of a seductive woman who gives birth to a child after the dance in a mysterious hotel in the middle of a forest.

At the Museum in Rimini, in Via Luigi Tonini, 1, you can see up close the Book of Dreams, a mishmash of images and words in which Fellini (taking the advice of psychoanalyst Ernst Bernhard) transcribed and illustrated his fervent dreamlike activity for about thirty years (from the 1960s to 1990); those “night journeys” later became pivotal in inspiring his films. There are two original albums, displayed in two showcases, while an anastatic edition can be browsed interactively.

Looking at those plates means entering Fellini’s inventive workshop from the main entrance, investigating his sources, watching ideas turn into films, seeing the figures and themes that would later populate them. To use his words: “Sink down into the abyss of the sea, down into the unconscious, fish in the unknown abyss of the sea and rise to the surface with treasures”. Or, to paraphrase Vincent van Gogh: “Dream the paintings and then paint the dreams”.