Enlightened businessman, versatile intellectual, liberal socialist, urbanist, philanthropist, publisher, essayist, and culturally voracious reformer: it is hard to put all of Adriano Olivetti’s genius pursuits into a box. Olivetti is known as a man who was able to inspire people, not only in his rural village of Ivrea but all of Italy, thanks to his avant-garde vision.

“You can do anything you want, except fire someone as a consequence of the introduction of new technologies ― involuntary unemployment is the most terrible evil that afflicts the working class.”

With these words, in 1932, Camillo Olivetti appointed his son Adriano, a chemical engineer just over thirty, as general manager of his company. His company, called Olivetti, was a leading computing company that had been founded twenty-four years earlier.

Fostered by paternal ethics and intrigued by the Fordist model, the young Adriano began to define his own business model early on in his life, combining technical competences, humanistic culture, global references, and local etymology.

After overcoming personal and historical obstacles caused by World War II, Olivetti’s “utopia” began to take shape: throughout his whole factory, he implemented a capillary renovation that stretched throughout the entire structure.

“Architecture is the form through which a certain type of society is expressed, while the other kinds of the arts are a free expression; a manifestation of the human spirit, independent from time and place.”

At the end of the 1930s, Olivetti commissioned Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini to design a residential neighbourhood that would accommodate the families of his employees. The result was the creation of a new, monumental building that housed increasingly busy workshops and offices. To fill these offices, Olivetti decided to choose employees with non-typical profiles to supervise each department. Through these appointments, he was able to bring fresh perspectives to the company.

Olivetti was looking for the perfect architectural balance: he believed infrastructures and natural landscapes should work together harmoniously within the same space. Further, the bright windows of the Olivetti establishment represented his desire to shed new light on manufacturing methods that had long been anchored to elite engineering know-how.

The literary critic Geno Pampaloni, writers Ottiero Ottieri and Paolo Volponi, and poet Giovanni Giudici walked by the Boogie-Woogie (a massive fresco created by Renato Guttuso, and situated at the factory entrance) every morning.

“The library, holding more than 50,000 volumes, holds records of cultural activities promoted by Adriano Olivetti: lessons about the history of the labour movement, conferences held by Pier Paolo Pasolini and Alberto Moravia, film festivals, exhibitions, concerts, and more.”

Even if these initiatives were often seen as the pipedreams of a utopian, Olivetti never lost sight of his goal to make a profit. Firmly convinced of the existence of a symbiotic relationship between industry and society, Olivetti supported the evolution of old production methods that had long burdened the staff, limiting its productivity.

By offering wages up to fifty percent higher than the Italian average, setting up a system of autonomous assembly islands, creating corporate nursery schools, granting nine months of paid maternity leave, making working hours flexible, and setting daily working limits, Olivetti saw his company’s earnings and prestige increase year after year.

“Functional, eye-catching, and selling at competitive prices, Olivetti’s products soon became icons of the “made in Italy” movement, supported by original advertising campaigns and packaged by the most talented designers in Italy.”

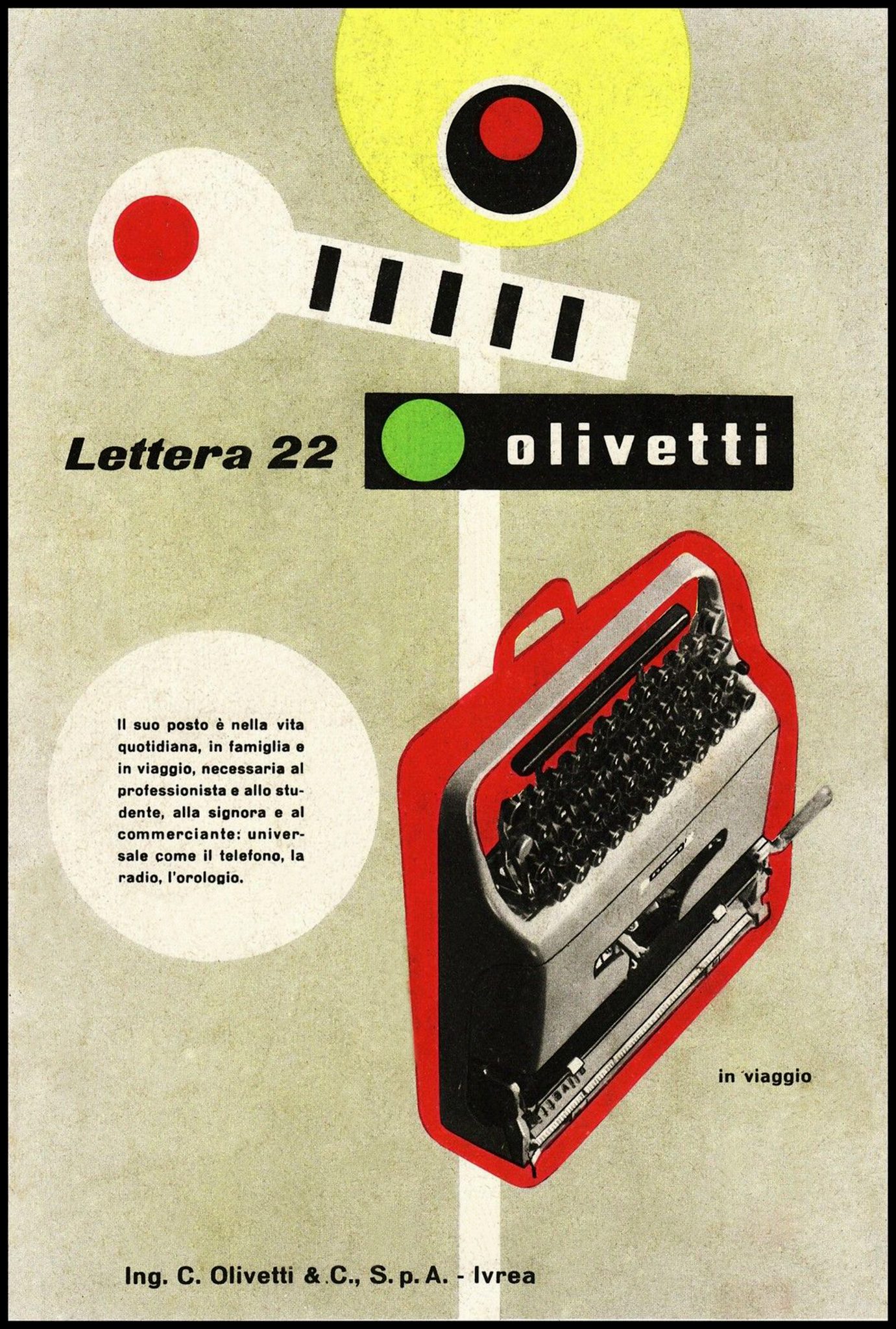

In Venice, at the wonderful Olivetti Shop ― designed by architect Carlo Scarpa in 1958 ― the famous Lettera 22 was for sale. The Lettera 22 was a nearly-perfect portable writing machine― it weighed less than four kilograms. The five rows of bleachers held forty-three keys ready to tap on a thirteen-millimeter fabric ribbon, shielded by the bold lines created by designer Marcello Nizzoli.

Awarded the Compasso d’Oro (“Golden Compass” award) in 1954, elected Best Product of the Century by the Illinois Institute of Technology, and permanently exhibited at the MoMA in New York, Lettera 22 is a prodigy of Italian industry. It is the best expression of the entrepreneurial taste of Adriano Olivetti, a failed utopian.

“Well, if I may say so, the term utopia is often the most convenient way to excuse what you do not have the urge, the ability, or the courage to do. A dream seems like a dream until you start working on it. And then it may become something infinitely bigger.”