When Italians say “That’s all very well” they are quoting the sports commentator par excellence, who gracefully and politely narrated Italy’s matches for over thirty years, becoming a real icon.

We are talking about the legendary Bruno Pizzul, an extremely competent and professional sports journalist. Generations grew up with Bruno along with their dreams and wishes. Pizzul’s was not just commentary, it was much more.

“The Rose Bowl is magnificent today. There are mainly Brazilian fans: yellow spots that bring our Italian brooms to mind,” said Pizzul before the 1994 World Cup final (Italy-Brazil) kick-off.

His wonderful voice really carried you on the pitch: it could make you live all ninety minutes. He did not just commentate ― he narrated matches, which is quite different. He spoke with the players during the comment, as if they could hear him.

“Dino, Roberto. Dino again, bravo,” he used to say every time Dino and Roberto Baggio played together for Italy.

But the audience was truly carried away when Bruno “told the deeds” of Italy’s number ten: six letters on his jersey under his long ponytail. Pizzul-Baggio was a historic combination.

“Then Zambrotta, Montella ― oh that’s good, Paolo, keep it down,” on a stop by Maldini.

Bruno Pizzul never got round to saying “World champions” because penalties killed an entire nation’s dreams in 1990, 1994 and 1998, when Di Biagio hit the crossbar, thus ending Cesare Maldini’s French World cup.

And four years later South Korea (and an Ecuadorian referee) kicked Italy out of the tournament in the round of 16 with a golden goal after much controversy.

2002 was the last World cup Bruno Pizzul commentated, who left without ever having narrated an Italian successful campaign.

But in Pasadena, in 1994, the only World cup final commentated by Bruno (who also commentated the Euro 2000 final, won by France against Italy after Trezeguet’s golden goal), Italians wanted to see Franco Baresi raise the Rimet cup, also to give due credit to the storyteller who had made them fall in love with the Arrigo Sacchi’s eleven that summer.

“We still have a faint hope; Roberto will take our last penalty: if he scores, we may hope that the Brazilians will miss their twelve-yard-shot. Roberto Baggio against Pagliuca ― sorry, against Taffarel. There goes Roberto: high!,” he commentates at the end of the 1994 World Cup in USA.

The Friulian journalist’s remains the true voice of Italian football. A nostalgic voice, an unmistakably pasty voice with perfect syntax and very precise vocabulary. A unique voice that could make images speak, as opposed to what often happens today.

Pizzul’s commentaries were pure magic, a mixture of melancholy and exaltation. The magical nights of the 1990 World cup in Italy were unforgettable, paired with the goals of the “boy from Palermo” Totò Schillaci:

“The cross comes in, and there’s the goal, Totò’s goal!,” In Italy-Austria during the 1990 World Cup.

On these evenings all Italians gathered in front of the TV, pouring the hopes of a lifetime into football in an attempt to dispel any kind of disappointment with a ball that rolled for ninety minutes.

And Bruno’s was the voice for Italians: every window of the Belpaese, in the warm Italian nights, rang clearly with the voice of the Friulian journalist.

Pizzul started playing football at an early age, displaying an immense body and a refined intelligence for the game on the field. He reached Serie B (League two) with Catania, but a broken knee ended his career.

He then studied law and later taught humanities in secondary schools. He then moved to RAI: his first commentary was on 8 April 1970, a Coppa Italia play-off on the neutral field of Como between Juventus and Bologna, where he incredibly arrived a quarter of an hour late.

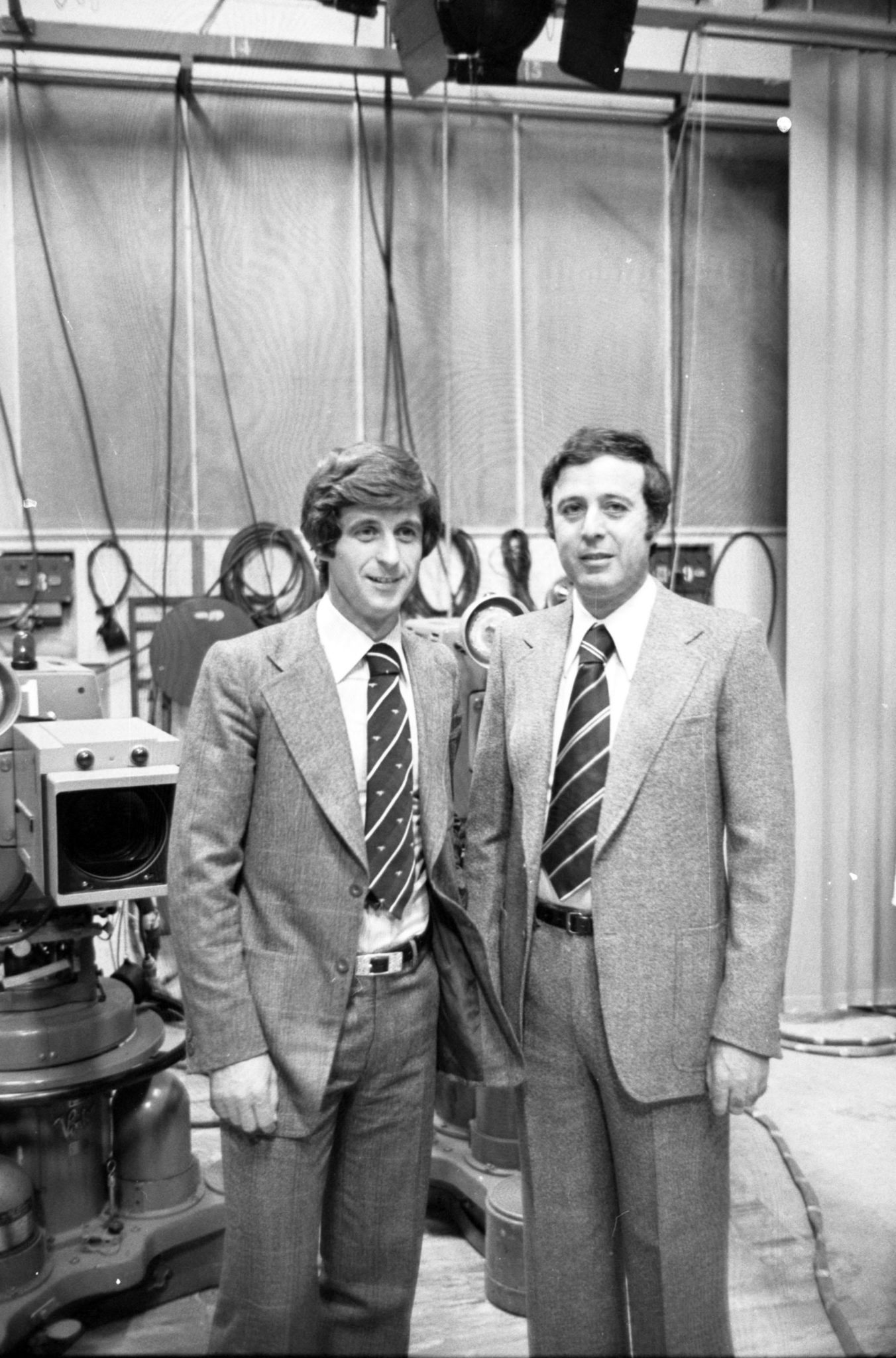

Pizzul learned to narrate football in Corso Sempione (Milanese headquarters of “Mamma RAI”) alongside Nando Martellini, whom he replaced during the 1986 World cup in Mexico.

He established himself as an inescapable presence: his style was part of the tradition of national TV, but as his colleague Bruno Gentili said, it shone for simplicity, clarity, and essentialness, which are the basic principles of oratory, but to which he added grace and that unmistakable tone of voice.

Pizzul managed to adapt to the evolution of football, to patterns, to tactics: in all cases, he never stopped narrating the game.

Now eighty, he still talks about football with enthusiasm and extreme precision, playing cards and drinking a glass of wine (strictly from Friuli).